How An Economic Recovery Could Become An Economic Catastrophe

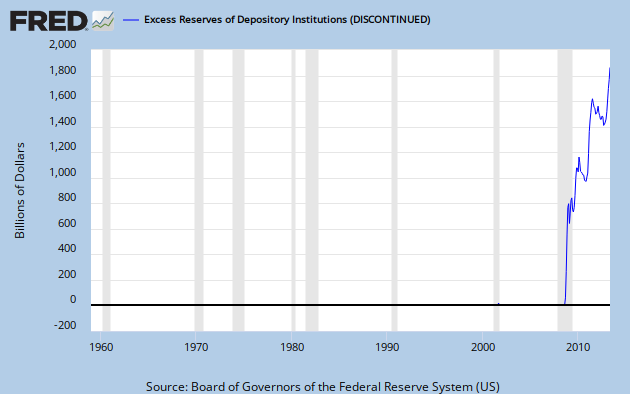

My friend, Jim Davidson sent me this chart yesterday.

Ok, clearly the chart above indicates that something unprecedented and drastic has been happening in our banking system for the past two years. But you are likely asking “what does this mean?”

The United States’ banking system is a fractional reserve system, meaning that banks are not required to hold 100% of the money deposited. Currently, the reserve requirement (the percentage of deposits that banks are required to maintain) is 10% for checking accounts. Thus, if you were to deposit $100 of your money into a checking account, the bank would legally be required to keep $10 and could lend out $90 to those borrowing money from the bank. Any amount they kept on hand above $10 would be considered “excess reserves.”

For those interested, the data used to make the above graph can be found here. A quick glance at either the data or the graph shows that for most of the past 50 years, banks have maintained reserves at levels very close to the levels mandated by the Federal Reserve. On August 1st, 2008, banks maintained excess reserves of $1.875 billion. One month later, excess reserves shot up to $59.482 billion. On October 1st, excess reserves equaled $267.159 billion, reaching $558.821 billion on November 1st, and $767.332 billion on December 1st. On April 1st, 2010 (the last date for which data is available), excess reserves totaled just over $1.05 TRILLION, or around 1000 times higher than they were 20 months earlier!

You are likely still asking what all this means.

Well…

What this means is that banks are keeping reserves on hand above and beyond the ratios required by the Federal Reserve. Banks are likely doing this for several reasons:

1) The banks know that many of they loans they initiated over the past several years are likely to default. These loans were purchased by these banks using the cheap credit made available by increases in the money supply and low interest rates. Thus, banks are keeping the “excess” capital on hand so that they can pay the interest on the money that they borrowed to make these faulty loans–even if there is a large number of loan defaults.

2) This ties in with the reason above, but these banks are worried about the consequences of asking for another large bailout from American taxpayers. The government bailed out these banks a year and a half ago, despite widespread public opposition and used the rationale that doing so would save the economy. However, since this bailout, the economy has only worsened. The banks know that it is unlikely that the American people would be as willing to allow their government to hand rich bankers taxpayer money again.

OK, so the banks arent lending right now, but what does this mean?

There is another major reason why the banks arent lending: we are in the midst of a pretty serious recession. No one knows how long it will last, and my guess is that no one really knows just how bad it is right now. With the exception of the Austrian Economists, not too many economists out there even say this crisis coming–much less lasting this long.

With so many people unemployed, so many businesses failing, and so few businesses expanding (or new businesses being opened), there just isnt a massive demand for loans. This gives banks another reason to continue to hold “excess” reserves.

But, the economy is slowly starting to pick up. As this happens, banks will begin to loan out more money and will eventually start to lower their reserves until they reach levels of excess reserves near the historical rate (in other words, near zero). In fact, it is already happening: On February 1st, excess reserves were $1.162 trillion, on March 1st, excess reserves were $1.120 trillion, and on April 1st, excess reserves were $1.05 trillion. In other words, banks decreased their excess reserves by about 9.6% between February 1st and March 1st.

As the economy recovers and banks make additional loans, this will increase the supply of money in the economy. An artificial increase in the supply of money is, simply put, not good. When there is more money in the economy chasing after similar amounts of goods and services, the result can be nothing else but an increase in prices (relative to what prices would have been without the increase in the money supply).

The effects of the increases in lending brought about by an economic recovery will increase the money supply by much much more than $1 trillion. As mentioned above, under our fractional reserve system, banks are only required to hold 10% of checking deposits and are able to lend out the remaining 90% to borrowers. However, the process doesnt stop there: if you deposit $100, the bank holds $10 and loans out $90 to someone else. When that person deposits their money in a checking account, their bank is then able to loan out $81 while only holding $9, and so on. As this process continues, banks effectively create (out of thin air) over 9 times the money that is held in their vaults and your $100 becomes nearly $1000 in the economy:

Thus measure of money supply is known as the M2 money supply. Thus, if banks return to their historical activities and maintain reserves at a level just above the reserve requirement rate, the result could be an increase in the M2 money supply of around $10 trillion. Currently, the total M2 money supply is just over $8.4 trillion, thus if banks start to lend out their excess reserves, the M2 money supply will more than double.

The implications of this are quite sobering. If the economy does not improve and continues to muddle along, things will be bad. Unemployment will remain high or possibly even creep higher, the stock market will continue to drop, people will continue to suffer and so on.

However, if the economy shows marked improvement and begins to accelerate, things will be much worse. At first, this might seem counter intuitive, but we must remember to take the above information into account. When the economy improves, banks will start to lend out their “excess” reserves. Because of the fractional reserve nature of the United States’ banking system, each dollar that banks hold in excess reserves has the potential to become nearly $10 when loaned out.

At first, this will make it look like the economy is growing at a very fast rate. After all, the newly created money is being spent by lenders to purchase things that werent being purchased before. The increased demand for these goods raises their prices (and initially the profits of the businesses selling these goods). This may result in a rise in wages for the employees in that sector of the economy. However, when monetary inflation occurs at a rate as high as the rates we are likely to see, this phenomena spreads throughout the whole economy. Thus, prices and wages will generally rise throughout the economy.

Anyone who thinks that this is a good thing is fundamentally wrong. We often are presented with the argument that increasing the money supply increases incomes and is necessary because without such increases “there wouldnt be enough money to go around.” As economist Tom Woods wrote in his best selling book, Meltdown, “It is to misconceive the nature and purpose of money completely to think its supply needs to expand in order to allow more transactions to take place.” In fact, in a system with a stable money supply, “prices fall over time and the value of money rises.” The reason for this is that “as output increases, the monetary unit simply gains in purchasing power.”

Monetary inflation (and the resulting price inflation) does not mean greater standards of living–the opposite is true. What monetary inflation does do is destabilize the economy, increase the inequality of wealth distribution, and make society less better off than it would be under a stable monetary system.

Just ask the citizens of Zimbabwe if the massive increase in their nation’s money supply have made them better off. In 1980, each Zimbabwe dollar was worth $1.59. After 30 years of constantly increasing the money supply, their economy is in shambles, and their money is worth less than the paper it is printed on. “In March 2007 Zimbabwe’s inflation rate passed 50% a month, a good threshold for defining “hyperinflation” and equal to 12,875% a year. Since then, it’s gotten much worse.” In late 2008, their price inflation rate reached the incomprehensible rate of “80 billion percent a month. That means around 6.5 quindecillion novemdecillion percent a year–or 65 followed by 107 zeros. To get a handle on it, realize that it’s equivalent to inflation of 98% a day. Prices double every 24.7 hours.”

Well then, if the argument that printing new money makes everyone in the economy better off has even a slight grain of truth in it, then Zimbabwe must be among the richest country in the world! After all, Zimbabwe is following the economic philosophy of the “brilliant” John Maynard Keynes and his disciples who have argued that increases in the money supply bring about prosperity by accelerating spending. Everyone knows that this is not the case, however. Zimbabwe is among the poorest nations in the entire world and recorded a 94% unemployment rate last January.

Does this same fate await America? Lets just say that something like this is possible. The Federal Reserve has been printing money for too long and has accelerated these practices in recent years and months. With a low reserve rate of only 10%, the Federal Reserve is just asking for trouble; when the economy recovers, things have the potential to spiral out of control quickly and result in a massive and destructive hyperinflation.

Yes, this can be slowed or even stopped. But, before you get your hopes up, ask yourself if the US government has ever learned from its mistakes or the mistakes of others.

Americanly Yours,

Phred Barnet

Please help me promote my site: